For something that dominates a few days of news cycle every year, the national budget is not particularly well understood. Media coverage tends towards giving headline updates from the governing parties press releases, which can sometimes be misleading. The document I’m primarily referencing in this episode is the expenditure report, which breaks down funding ceilings by government department. It’s also important to point out that something being written into the expenditure report in no way guarantees that it will happen in the coming year or at all.

This is not to say that the budget doesn’t matter. It does still highlight the government’s priorities and if a project has a low expenditure ceiling or limit, then it is unlikely that will change post-budget. If something is not even mentioned, then it clearly isn’t prominent in the government’s awareness or objectives. A Programme for Government is even less binding. It’s only a document published by parties forming a coalition government in order to clarify the joint platform that they have agreed to form that coalition on. The significance doesn’t come because we expected it to be entirely accurately, but that it matters what they bother to lie about.

My original intention was to have a budget episode out shortly after it was published, but given that the general election came immediately afterwards, I decided to wait. I wasn’t interested in framing it in the context of who anyone should vote for. There is also a real danger on making climate or environmental issues into binary questions, not only because it polarises discussion into us and them, but because there is rarely only one policy solution to achieve a goal. There is usually, if you’ll pardon the phrase, more than one way to skin a cat.

Following the general election, the majority of TDs that had been in the government before were elected again, with the exception of the Green Party. The government currently being formed between Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael, and a number of independents is not a major departure from the previous government and so I think that Budget 2025 is still a relevant document to compare to the Programme for Government that the coalition just released. In fact, there is such a sense of status quo with this PfG that the word “continue” is the sixth most used word, appearing 226 times in just 138 pages of text.

Beginning with the expenditure report released in October just gone. The relevant numbers are the Ministerial Group Vote expenditure ceilings, which are broken down by department. Within each department there are two types of expenditure, current and capital, and then there are the programme streams. Current expenditure refers to staffing, operational budget, etc. Capital expenditure refers more to acquisitions, meaning the purchase of goods, property, land, and infrastructural investment. Those are obviously big umbrella terms, but when looking for specifics it’s important to get to each departments named programme streams and see if there is any further funding breakdown.

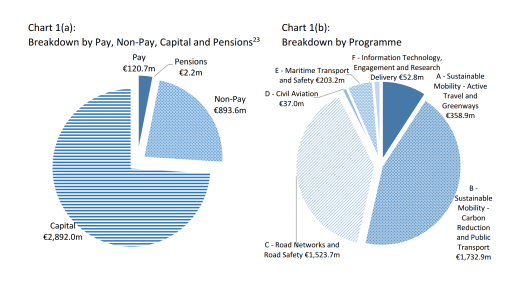

A good example to use is the Department of Transport. The expenditure ceiling for Transport is 3.9b euro, of which just over 1b is current expenditure and just over 2.89b is capital. It makes sense that a department dealing primarily with public infrastructure would lean heavily towards capital expenditure in its budget. There are six programmes titled A to F described under transport and each is given its own allocation of funds. The two largest are Programme B Carbon Reduction and Public Transport which is allocated €1.7b and Programme C Road Networks and Road Safety with €1.5b. Combined public transport and roads make up 83% of the Transport budget, which also makes sense. The other four programmes that make up the remaining 17% are active travel and greenways, civil aviation, Maritime Transport and Safety and Information Technology. Each of the programmes has a small further breakdown paragraph of text but usually figures aren’t applied here.

Hopefully that gives you sense of the structure of the reports.

The obvious department to start with is Environment, Climate & Communications. This brief has been changed and moved around quite frequently in cabinet reshuffles. I’ve mentioned before in episode 6 on environmental law and state agencies in Ireland that there have been legacy issues coming from agencies being moved around. Often changes to departments at a cabinet level are political and optics based, and they aren’t always entirely reflected within the civil service on an operational basis.

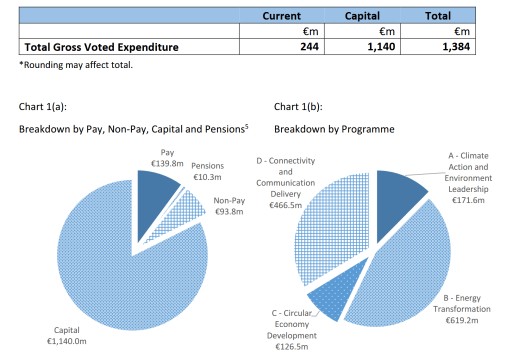

The 2025 expenditure ceiling for Environment, Climate and Communications is €1.3b, of which 1.1b is capital expenditure. Like transport this isn’t surprising since this is a small department at an administrative level but involves large infrastructure projects like broadband and renewable energy.

I found the programme breakdown in this department a bit baffling. On a headline level they are Programme A: Climate Action and Environmental Leadership, B: Energy Transformation, C: Circular Economy Development, and D: Connectivity and Communication Delivery. Programmes B and D take up 78% of the budget, since they are the ones with the most capital expenditure, but breaking the department down into these four programmes misleads the reader about how prioritised the other two projects are.

Working backwards for a moment, programme D on connectivity and communication, that’s largely a communications infrastructure project and programme C on the circular economy is a bit notional in places though it does confusingly include the funding for the agency Inland Fisheries Ireland. Why Inland Fisheries in being budgeted under circular economy I really couldn’t say.

There are some similar levels of jargon around Programme A – Climate Actions and Environmental Leadership. Allocated €171.1m that will to used to:

i. Contribute to international climate commitments, as set out by the All-of-Government International Climate Finance Roadmap 2022.

ii. Continued support to those sectors of the economy most impacted by the transition to net zero emissions through the EU Just Transition Fund.

iii. Provision of resources and support to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

What this doesn’t tell us is how that 171 million is broken down, how much is for the EPA and how much additional can be drawn down through the EU Just Transition Fund, etc. The EPA is a state agency, as I mentioned above, meaning that it functions independently to the rest of the department civil service, reporting to the relevant minister. While some agencies like the EPA are clearly defined by law, there are others that not statutory agencies and more like branded working groups within the department. Irish Aid functioned like this within the department of foreign affairs for many years. People often assumed it was an independent state agency, but it wasn’t.

Programme B, Energy Transformation is allotted €619.2m and that is broken into four main goals:

- €469 million from Carbon Tax revenue for residential and community energy upgrades (including Solar PV) to support the delivery of the National Retrofit Plan.

- Energy research

- national and EU climate and energy ambitions, specifically targets for offshore renewable energy.

- Resource the Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland (SEAI) another state agency

That all sounds good, but there are a few crucial issues at play. First the mention of the Carbon Tax revenue. The efficacy of carbon taxes aside, there is a general understanding that this money is ring-fenced to de-carbonised our infrastructure and economy, but questions as to whether that is true have been raised recently.

In September 2024 Deputy Brian Stanley raised some issues around this during Dáil questions. He was chairperson of the public account committee, sometimes called PAC, at the time. This was coming from the 2023 Report on the Accounts of the Public Service, published by the Comptroller and Auditor General, the C&AG. For a long time, I thought people were saying CNAG, because who puts an ampersand in the middle of an acronym? This is the kind of torture that I endure on this podcast, so that you the listener don’t have to.

The Report on the Accounts of the Public Service is a crucially important document if you’re trying to understand government spending but because accounting is that fatal combination of boring and difficult, it got little to no media coverage. I, brave dyslexic soldier that I am, waded in nonetheless.

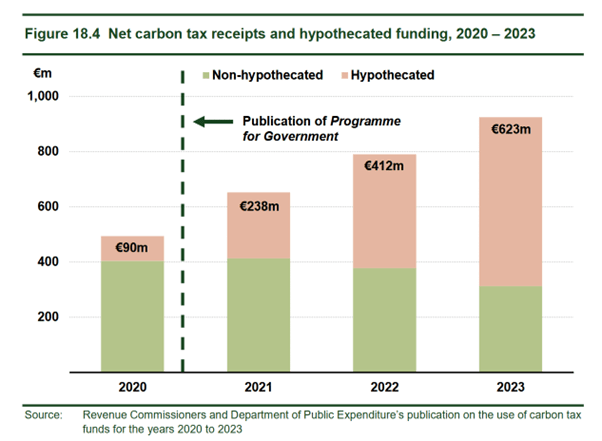

Within the section on carbon tax receipts, we get to page 291 Hypothecation of carbon tax funds which meant I learned a new word. Hypothecation means a situation in which money from a particular tax is only spent on one particular thing, more commonly referred to in policy as ringfencing funding.

On my website I always put a text version of every episode up, but this one in particular has graphs that help illustrate some of what I’m saying. The report is far too detailed for me to read aloud to you here, but fundamentally hundreds of millions of euro from the carbon tax annually goes unspent as part of the ringfenced programmes and is surrendered back to the Exchequer.

Just in the department we’re discussing, Environment, Climate and Communications of the €660.5 million allocated between 2020 and 2023, €178.4 million remained unspent at the respective year-ends and was surrendered back to the Exchequer. That’s 27% of allegedly ringfenced funding for goals and targets that are absolutely not being met somehow not finding somewhere to spent? That doesn’t seem creditable to me.

Even where it is being spent, it’s being allocated in departments for projects that were already part of social welfare, like a winter fuel allowance, and labelling that part of “Just Transition” when its barely connected. It isn’t that I don’t think the department of social protection should be making sure people can heat their homes, but I do think that it’s a stretch to call it part of decarbonising our economy.

Another way these headline declarations do not seem borne out in reality is that the grants for PV solar panels have gone down. €2400 was available from the SEAI in 2023 and only €1800 is on offer now.

The Programme for Government opens its environment section on page 50 by claiming that the new government will achieve a 51% reduction in emissions from 2018 levels by 2030 and net-zero emissions no later than 2050. This is a fun piece of mathematic distraction since the vast majority of people have no idea what the emissions of 2018 were or how far we’ve already reduced them to understand how ambitious that 51% might be.

Ireland’s emissions in 2018 were 60.93 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent. Like I discussed in episode one, all the various greenhouse gases are converted into the carbon dioxide equivalent effect to simplify figures. In 2023 those emissions fell by 10%, to 55.01 million CO2 eq. In order to reduce 51% from 2018, Ireland would have to reach 29.86m CO2eq. To call that ambitious would be an understatement. I would be very excited by those figures if they had any basis in reality, given the measures actually put in place, which according to our own Environmental Protection Agency we are not even close to. Our EU targets are based off a 42% reduction on our 2005 levels and so that further muddies the waters.

I want to pause in reciting numbers here, because I think it can become meaningless statistical soup after a while. These constantly shifting goalposts, 50% percent of one or 40% percent of another, make it almost impossible for someone who is not making this their day job to comprehend. This is my day job and I still had to dig through a stack of documents, reports and national plans to get to real numbers.

So, to reiterate, the Programme for Government claims a carbon emission target of 29.86m CO2eq by 2030, a 45.7% reduction from 2023 and a staggering 58% reduction on 2005 (which was 71.21m tonnes). I emphasise these EU targets stemming from 2005 because in May last year, 2024, the EPA projected that the government’s currently implemented measures would achieve a reduction of only 9% on 2005 levels by 2030 and even with more ambitious measures than they had in place (which we have not seen) the EPA still only predicts a best-case scenario reduction of 25% by 2030. There is nothing in this PfG that could possibly more than double that estimate. It is not simply poor use of statistics; it is an outright lie.

The following four pages on energy and emissions swings wildly between some sensible policies, retrofitting homes or creating clusters of localised renewable energy generation, and on the same page trying to make allowances for biogenic methane and highlighting the importance of data centres for the economy.

The area we see more divergence between budget 2025 and the Programme for Government is in the area of heritage and biodiversity. As sceptical as I have been about the Green Party’s influence in the previous coalition, I do want to give a certain amount of due credit to Malcolm Noonan’s efforts here. I was critical of many of the decisions made, but this demonstrates that he must have been applying some pressure internally. Issues of heritage and biodiversity, due to another of those pesky cabinet reshuffles, ended up in Housing, Local Government and Heritage.

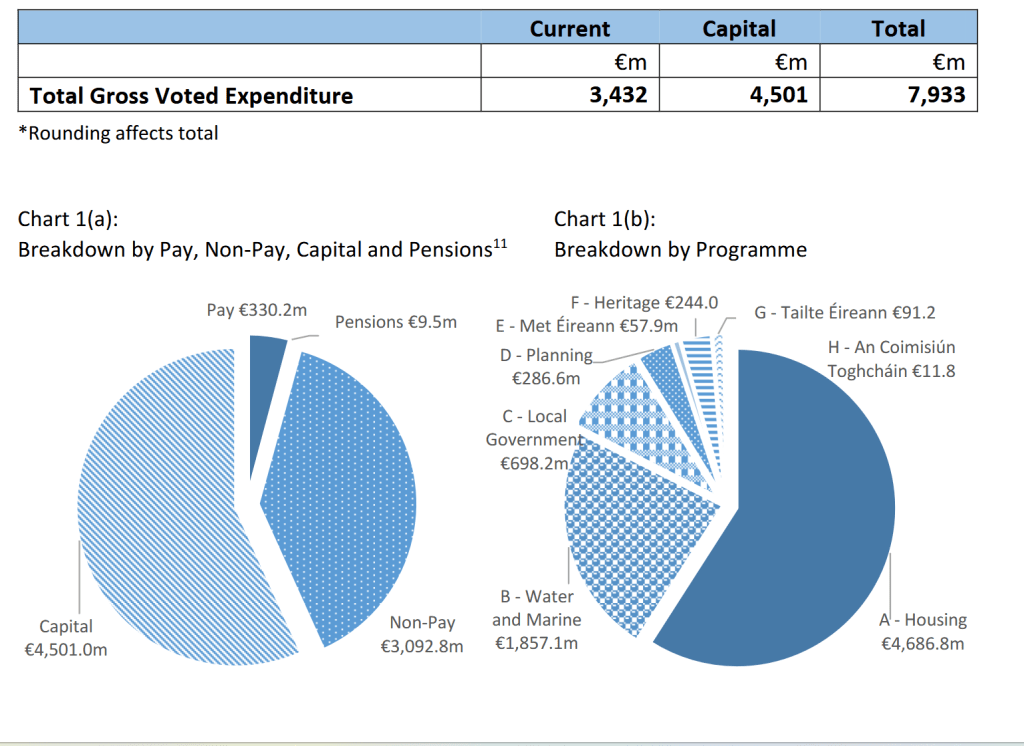

Obviously, the bulk of this departments €7.9b is allocated to housing, but the pie chart breakdown of funding on page 108 shows €1.86b for water and the marine and €244m for heritage.

This however is contradicted a few pages later when the programme stream description claims that heritage is only receiving €177m. While typos do happen, I think all of us would like to know where that €67 million ended up.

Programme F: Heritage has a significant list of goals for an area with 177m in the text of which 82m is current expenditure and 95m is capital. It calls for serious renewal of the NPWS, increased resourcing of the Heritage Council and the National Biodiversity Data Centre. There was significant mention of various EU programmes, the Nature Restoration Law as well as Habitat and Bird’s Directives. It called for increasing the capacity to prosecute wildlife crimes, but the word staffing or capacity was pointedly never used in relation to the NPWS.

Meanwhile the Programme for Government’s section on Heritage & Nature on page 57 does not mention the EU at all. The Nature Restoration Law is referenced, but it is linked to the National Biodiversity Plan and not the fact that it is an EU wide initiative. There was one interesting suggestion of the government creating “an NPWS internship programme encompassing traditional skills, ecology, wildlife rangers and advanced nature research” but again no mention of staffing. There was an emphasis on creating national parks and acquiring heritage assets over capacity building in existing ones, but it’s hard to say what the rationale for that was in such a short section. Invasive species did get a mention, though that was one of the many “continues”, as in “Continue to invest in managing the spread of invasive species.” Since the current state of affairs is bad, maybe the idea of carrying on as is, isn’t as appealing as they hoped.

Programme B in heritage in Budget 2025 is Water. Of the €1.86b allocated here, over 1.7 of it is being provided to Uisce Éireann to meet the cost of domestic water services. Uisce Éireann, formerly Irish Water and also currently Irish Water to anyone with a dictionary is probably one of the laziest attempts at rebranding in the modern era. The €146m being provided to support other water programmes, apparently includes the new Rural Water Programme, investment in legacy issues (such as lead piping and problematic stand-alone wastewater treatment systems); a wide range of environmental programmes related to the Water Framework Directive, including a river restoration programme; and work in the Marine Environment, including the development of Marine Protected Areas. There are two major questions arising here. If the other water programmes are doing all that, what on earth is Uisce Éireann doing? Also how is there funding allocated for Marine Protected Areas, a statutory designation that does not exist, because not only did the previous government not pass MPA legislation, they did not even draft it. Bizarrely, MPAs are also in the PfG. Page 29 on the marine claims they are going to “expand” Marine Protected Areas, which is difficult to do without any being created.

There is honestly too much to say on agriculture to do justice in this episode. This section of the Programme for Government was particularly telling. This was where the “continues” were very prevalent. The language around beef and dairy was focused on growth though tellingly it said the government intended to “maintain the Organic Farming Scheme” rather than expand it. Budget 2025 allegedly has €712m set aside for agri-environment schemes but this term is used very loosely, as it includes environmentally damaging forestry practices and “beef, sheep, and dairy”. Some of that funding is coming from the carbon tax revenue discussed earlier. Two other “continues” were retain the current forestry programme and retaining the nitrates derogation discussed in episode 5.

There is a particular disingenuous aside in the nitrates section about developing “evidence-based solutions” for water quality in rural areas, obviously trying to imply that the continuous evidence that nitrates from agriculture are the biggest pressure on water quality are false somehow and they need new research that gives them the answers they want to hear. It also tells you everything you need to know about the way in which they are pandering that the commitment to “continue” support for the Horse and Greyhound racing funds in the agriculture section and not heritage or tourism.

Two positives out of the agriculture section of the PfG were continued opposed to the Mercosur trade deal at an EU level and investigating the “feasibility of a scouring plant for wool in developing an Irish wool brand”. It might seem counterintuitive, but something that brought value to fleeces would change how sheep were kept. In marginal areas of low value farming, with flocks grazing poor quality commonage or the uplands, often with low levels of supervisor or management, that’s where overgrazing is particularly intense. If the quality of the wool mattered, it would likely change some of these behaviours, though I do think the details of sheep farming and grazing, particularly in the north-west, is a larger topic for another day.

Episode 10 Sources

Comptroller and Auditor General (September 2024) The 2023 Report on the Accounts of the Public Service

Government of Ireland (2024) Budget 2025

Department of Environment, Climate and Communications (4 July 2023) Press Release: Ministers Ryan and Coveney announce enhanced supports for business through Solar PV Scheme

EPA (2024) Ireland’s Final Greenhouse Gas Emissions 1990 – 2022

EPA (2024) Ireland’s Provisional Greenhouse Gas Emissions 1990 – 2023

EPA (2024) Latest Emissions Data (accessed 18 January 2025)

SEAI (2025) Solar Energy Grant information